BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerAs the new Syria struggles to take shape, old threats are resurfacing.

The chaos that followed the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad is “paving the way” for the so-called Islamic State to make a comeback, according to a senior Kurdish leader who helped defeat the jihadist group in Syria in 2019. The comeback has already begun.

“ISIS activity has increased significantly, and the risk of its resurgence has doubled,” said General Mazloum Abdi, commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces, an alliance of US-backed Kurdish militias. “They have more capabilities and more opportunities.”

He added that ISIS fighters seized some weapons and ammunition left behind by Syrian regime forces, according to intelligence reports.

He warns there is a “real threat” that militants will try to storm prisons run by the Syrian Democratic Forces here in north-eastern Syria, which are holding around 10,000 of their men. The Syrian Democratic Forces are also detaining about 50,000 of their family members in camps.

Our interview with the general was late at night, in a location we cannot disclose.

He welcomed the fall of the Assad regime, which arrested him four times. But he looked exhausted and admitted frustration at the prospect of fighting old battles again.

He added, “We fought them (ISIS) and paid 12,000 lives,” referring to the losses of the Syrian Democratic Forces. “I think at some point we will have to go back to where we were before.”

He says the risk of an Islamic State resurgence is increasing because the SDF is under increasing attacks from neighboring Turkey — and the rebel factions it supports — and must divert some fighters to that fight. He tells us that the Syrian Democratic Forces were forced to halt counter-terrorism operations against ISIS, and hundreds of prison guards – from a force of thousands – have returned home to defend their villages.

Ankara views the SDF as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), the outlawed Kurdish separatists who have been waging an insurgency for decades and are classified as terrorists by the United States and the European Union. It has long wanted to establish a 30-kilometre-long “buffer zone” in the Kurdish region in northeastern Syria. Since the fall of Assad, it has been striving to achieve this.

“The first threat now is Türkiye because its air strikes are killing our forces,” General Abdi said. “These attacks must stop, because they distract us from focusing on the security of detention centers, although we will always do our best,” he said.

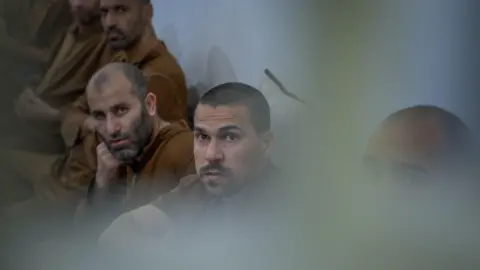

Inside China Prison, the largest prison for ISIS detainees, we saw the layers of security and felt the tension among the staff.

The former educational institute in the city of Hasakah houses about 5,000 men – suspected fighters or ISIS supporters.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerEach cell door is locked and secured with three screws. The corridors are divided into sections by heavy iron gates. The guards were masked and carrying batons in their hands. Getting here is rare.

We were allowed to peek inside two cells, but we were unable to speak to the men inside. They were told we were journalists and were given the option to hide their faces. Few did. Most of them sat silently on the blankets and thin mattresses. Two men walking on the ground.

Kurdish security sources say that most of the prisoners in China's prison were with ISIS until its last battle and were strongly committed to its ideology.

They took us to meet a 28-year-old detainee. He was thin, spoke in a low voice, and did not want to reveal his name. He said he spoke freely, although he did not talk much about major issues.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerHe told us he left his native Australia at the age of 19 to visit his grandmother in Cyprus.

“From there, one thing led to another, and I ended up in Aleppo,” he said. He claimed that he was working with an NGO in the city of Raqqa when ISIS took control of it.

I asked him if his hands were covered in blood and he was involved in killing someone? “No, I wasn't,” he replied in a barely audible voice.

Did he support what ISIS was doing? He replied: “I do not wish to answer this question because it may have an impact on my condition.”

He hopes to return to Australia one day, although he is not sure whether he will be welcomed.

There is also hope behind the wire of Camp Rouge – about a three-hour drive away – that freedom is coming. somehow.

This bleak expanse of tents – surrounded by walls, fences and watchtowers – houses nearly 3,000 women and children. They were never tried or convicted, but they are the families of ISIS fighters and supporters.

There are many British women in the camp. We met three of them briefly. They all said their lawyer asked them not to speak.

In a windswept corner we came across a woman ready to talk – Saida Temirbulatova, 47, a former tax inspector from Dagestan. Her nine-year-old son, Ali, stood quietly beside her. She hopes that Assad's ouster will mean freedom for both of them.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael Steininger“The new leader, Ahmed al-Shara (head of the Islamic group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham), gave a speech in which he said that he would give everyone their freedom. We want freedom too. We want to leave, most likely to Russia. It is the end.” “The only country that will receive us.”

The camp director tells us that others believe that ISIS will come to their rescue and smuggle them out. She asked us not to use her name because she fears for her safety.

“Since the fall of Assad, the camp has become quiet,” she said. “Usually, when it is quiet, it means that the women are organizing themselves.” “They have packed their bags ready to go. They are saying: We will leave this camp soon and renew ourselves. We will return again like ISIS.”

She says that there is a clear change, even among children, who chant slogans and curse passers-by. “They say: We will come back and take you. They (ISIS) will come soon.”

During our time at camp, several children raised the index finger on their right hands. This gesture is used by all Muslims in daily prayer, but it is also widely used by ISIS fighters in propaganda images.

The women in Roj camp are not the only ones packing their bags.

Some Kurdish civilians in the city of Hasakah are doing the same, fearing the return of jihadists and another ground attack by Türkiye in northeastern Syria.

Jiwan, 24, who studies English, is getting ready to go – reluctantly.

“I packed my bag, and I’m preparing my ID and important papers,” he tells me. “I don’t want to leave my home and my memories, but we all live in a state of constant fear. The Turks threaten us, and the doors are open to ISIS. They can attack their prisons. They can do anything.” “They want.”

Joan was once displaced from the northwestern city of Aleppo, at the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011. He wonders where to go this time.

He says: “The situation requires urgent international intervention to protect civilians.” Ask if he thinks it will come. “No,” he answers quietly. But he asks me to state his argument.

Additional reporting by Michael Steininger and Matthew Goddard