BBC Middle East analyst

Reuters

ReutersHistorical buildings are reopened in Mosul, including churches and mosques, after years of destruction resulting from the acquisition of the Iraqi city by the extremist Islamic group (IS).

The project, which was organized and funded by UNESCO, began a year after a defeat and expulsion outside the city, in northern Iraq, in 2017.

UNESCO Director -General Audrey Azoulay and Iraqi Prime Minister Muhammad Xia Shi'a will attend the audience on Wednesday to celebrate the reopening.

Local craftsmen, residents and representatives of all religious societies in Mosul will be there.

In 2014, Mosul, which was seen for centuries, is occupied as a symbol of tolerance and coexistence between different religious and ethnic societies in Iraq.

The group imposed its extremist ideology on the city, targeting minorities and killing opponents.

Three years later, a US -backed coalition in an alliance with the Iraqi army and the militia -related militias made an intense attack and an air attack on the city's return to control. The bloodiest battles focused on the old city, where the group's fighters took a final position.

Mosul's photographer Ali Baroudi remembers the horror he received when he entered the area for the first time after the end of the street battle in the summer of 2017.

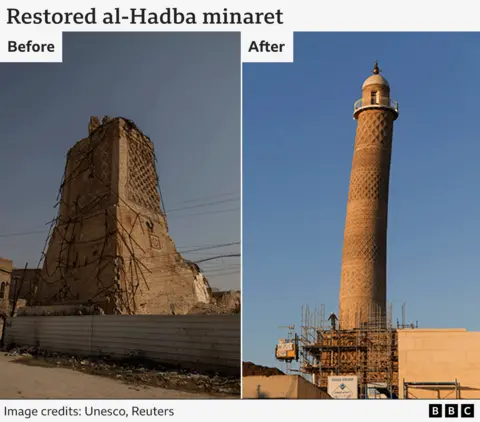

He saw that the glorious curved curved, known as “Al -Hadhab”, which was a symbol of Mosul for hundreds of years, in ruins.

He says, “It was like the city of ghosts.” “The bodies are everywhere, a sick smell and horrific scenes of the city and the horizon without hapba minaret.

“The city we knew – was like the transformation – we never imagined even in our worst nightmares. After that, I was silent for a few days. I lost my voice. I lost my mind.”

Eighty percent of the ancient city of Mosul was destroyed on the West Bank of the Tigris Tigris, during the three -year occupation.

The churches, mosques, and ancient homes that needed to be fixed were not, but also the spirit of society for those who lived there for a long time in a relative harmony between religions and races.

The huge task of reconstruction under UNESCO started with a budget of $ 115 million (93 million pounds) that the agency managed to advance, and many of them from the United Arab Emirates and the European Union.

Father Olivier Bokilon – Dominican Priest – returned to Mosul to help restore one of the main buildings, Deir Notre Dame de L. .

He says: “We started trying to collect the team first – a team consisting of people from ancient Musaul from different sects – Christians and Muslims who all work together.”

Father Bokilon says that the collection of societies together was the biggest challenge and the largest achievement.

“If you want to rebuild the buildings that you have first to rebuild confidence – if you do not rebuild confidence, it is not worth building the walls of those buildings because they will become a target for other societies.”

The entire project official – which included the restoration of 124 old houses and two wonderful stories – was the main architect Maria Rita Asetoso, who came to Mosul directly from UNESCO's restoration work in Afghanistan.

“This project explains that culture also can create job opportunities, and can encourage skills development, in addition to that, those concerned can make part of something meaningful,” she says.

She hopes that reconstruction can restore hope and enable the bake's cultural identity and its memory.

“I think this is especially important for young generations that have arisen in setting conflict and political instability.”

UNESCO says more than 1,300 local youth have been trained in traditional skills, while about 6000 new jobs have been created.

More than 100 semesters have been renewed in Mosul. Thousands of historical fragments have been recovered and indexed from rubble.

Among a group of engineers participating in rebuilding, 30 % of women were.

Eight years later, the bells go again through Mosul from the church, whose ceiling collapsed after severe damage under the occupation in 2017.

The other main features of Mosul-km, which are shouting in Al-Hadba, the Dominican Monastery, and the Al-Nuari Mosque Complex.

People were able to return to the homes that were home to their families for centuries.

One of the residents said, Mustafa said:

“So I decided to move to my father's house. I was very pleased and excited to see my home rebuilt again.”

EPA

EPAThe Abdullah family also lived in a house in the old city since the nineteenth century when the area was a center for wool trade – this is why their house is precious to them.

“After building UNESCO, I went back,” he says. “I cannot describe the feeling I felt because after seeing all the destruction that happened there, I thought I would never be able to return and live there again.”

The scars of what the people of Mosul have yet to heal – just as many remain in a fragile state of Iraq.

But the birth of the old city of the rubble represents hope for a better future – as Baroudi continues to document the development of his beloved house day after day.

“It is really like seeing a dead person returning to life in a very beautiful way – this is the true spirit of the city that dates back to life.”