Princess Tricia Nobani

Princess Tricia NobaniAt the age of 60, Nigerian businessman and healthcare professional Ken Okoroafor has fulfilled his childhood dream of earning the revered title of “Cheetah Killer.”

Jubilant crowds gathered as he joined the prestigious all-male Igbo association in his hometown of Ojota, in south-eastern Nigeria.

In ancient times, slaughtering a tiger was not just an act of bravery, but a ritualistic act that conferred societal prestige.

To become a “tiger killer,” known as “ogbuagu” in the Igbo language, a man had to offer a tiger—which he hunted and killed himself—to the local king. Its meat was then shared among 25 villages around Oguta.

Over time, this practice evolved, and people no longer needed to hunt the tiger themselves.

My mother remembers the tiger carcass lying in the living room in 1955 when her father received the title. It was captured by a professional hunter.

She recalls eating tiger meat twice in the past: “It tastes wild and a bit salty.”

Conservation concerns then led to an end to the use of cheetahs as they became rare in the region. The last known sacrifice of a cheetah occurred in 1987.

Once widespread throughout Nigeria, cheetahs now tend to be found only in a few national parks, where they are protected.

Today, the financial equivalent – a large but undisclosed sum – is distributed among the heads of households in the 25 villages, keeping alive the communal spirit of this tradition.

“In Oguta, when you join this community, you get respect and you join them in most of the decision-making processes in the city,” said Okoroafor, who lived in the United States for decades but returned to his roots to become an Ogbuagu.

“It attracted me. It's something I've been hoping to join since I was a little kid.”

The first recorded use of money as a substitute dates back to 1942 when a man named Mbirikebe Ojirika hunted a tiger at a ceremony, but then his mother died.

Tradition states that Ojirika must mourn for six months and cannot continue with this ritual. When he later tried to find another tiger, he failed.

Realizing the difficulty, his relative, Eze Igwe – the traditional king of Oguta – allowed him to pay four shillings instead of offering him a tiger.

“From that time, you now have the option of using money or cheetah,” said 52-year-old Victor Anish, current secretary of the Igbo Association, and Ojirika’s grandson.

“When I made my own tiger in 2012, someone offered to bring me a live tiger from northern Nigeria,” said Anish, a mechanical engineer and engineer. “They had one to sell to me. But I couldn’t imagine killing an endangered animal.” Graduate of Cambridge University.

But the path to becoming Ogbuajo today remains difficult, involving three complex stages.

Princess Tricia Nobani

Princess Tricia NobaniThe Igbo Association – which currently has about 75 members – is as old as Ogota itself, with roots dating back more than four centuries since the city was founded by immigrants from the ancient Kingdom of Benin.

Despite their Igbo ethnic classification, the Oguta people retain a distinct identity. Their dialect, customs and traditions set them apart from the local population and expatriates whose number is estimated by various sources at approximately 200,000.

Many of those who want to become Ogbuagu choose to attend their celebrations during the festive Christmas season, allowing families and diaspora communities to come together, often attracting large crowds.

On December 21, Zobi Ndubo, a rock physicist who works in Nigeria's oil sector, begins his first phase of becoming a “cheetah killer” – known as “Igbo Agu” – when the hunt is re-enacted.

The day began at 09:00 a.m., with the Ogbuagu gathered in a large tent at Mr. Ndubu's house. They greeted each other with the sounds of their golden swords and exchanged pleasantries.

Although Eze Igwe does not attend public events, he sent his representative to join the ceremony.

The Ogbuagu sat in hierarchical order, which was determined by the date on which they became full members.

Women were not allowed to touch the oguagu, enter the assembly or participate in the ceremony, but I watched from nearby.

The Ogbuajo people ate traditional dishes such as peppery goat meat soup, nisala soup – made with catfish – ground yams and palm wine.

During the ceremony, Mr. Ndobo was summoned by the secretary: a palm frond was tied on his wrist, chalk marks were drawn on his hand, and he was given a new, gold-coloured sword engraved with his name.

He then moved around the assembly, saluting each Ogbuajo and striking his sword with theirs four times.

In the afternoon, after the feast, Mr. Ndubo was escorted from his home in procession. The “Cheetah Killers” walked in a hierarchical order, with the new initiate, Mr. Ndubo, stationed at the end of the line.

Princess Tricia Nobani

Princess Tricia NobaniThe group headed to Eze-Igwe's palace, where they gave the king money in exchange for the tiger.

The second stage, known as “Iga Aji”, is a spiritual portion that is conducted privately at the initiate’s home – in the presence of members of the Igbuu Association.

During this stage, the initiate is given a red sash symbolizing royalty, as well as sacred beads and feathers.

After receiving his red scarf, Mr. Okoroafor went to greet his relatives who had gathered in tents outside. They celebrated it with chants of “Ogbuagu!” While they were eating and drinking.

The final stage, “Ipu Afia Agu,” is a grand feast that represents the initiate’s full membership. The celebration begins at the home of the initiate's mother and then moves to his private residence.

This is the most expensive stage, and often includes livestock, aquariums and liquor crates to entertain hundreds of guests.

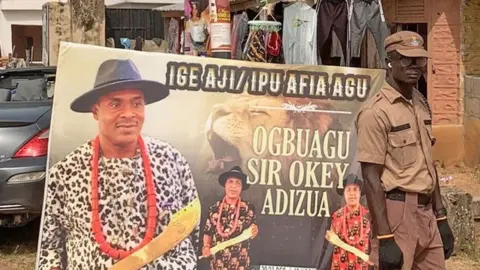

After a recent meeting at his mother's house, Pascal Oke Adezua, a 60-year-old car dealer from Maryland in the US, was paraded around town holding aloft the symbolic fake leopard skin.

Accompanied by the Ogbuajo, chanting women and lively music, his new status was celebrated by dancing, singing and feasting shared by all.

Mr Adezua completed his first phase in 2023 but chose to wait until last December to complete phases two and three so that his two daughters – two doctors and a nurse – could attend.

“My children have finished school,” said Adesuwa, who has lived abroad for 21 years. “The last child is the only one in university. A lot of my friends have come from the United States.”

Both Mr Adizua and Mr Okoroafor, who completed phases two and three in December, can now enjoy the unparalleled prestige that comes with Igbuu membership.

The “Leopard Killers” are addressed by their nickname “Ogbuagu” throughout Igboland – and beyond.

In Oguta, only they can stand and salute the king without bowing. Their presence is respected at all occasions such as weddings where they are given seats of honor.

Ceremonial beads worn on the right wrist identify the Ogbuajo, and symbolize their status. On traditional occasions, they must wear specific clothing.

“The title ‘Ogbuagu’ is a complimentary name,” explains Mr Anish. “If you can go into the jungle and hunt down a tiger and kill it, you are a warrior.”

Igbo leadership follows a strict hierarchy, with seniority based on an individual's tenure, not age. The longest serving member holds the highest leadership position. The current leader is Emmanuel Odom, who is now in his early eighties.

In addition to the president, who oversees the group's affairs and meetings, Igbo members nominate and elect officials to handle day-to-day operations and management. Mr. Aniche has served as Secretary for the past four years.

“We have members in their mid-40s to 90s,” Mr Anish said.

Some of Ogbuajo’s notable figures include the late Chukwudifo Oputa, one of Nigeria’s most respected Supreme Court justices; Alban Uzoma Nwaba, a Swedish-Nigerian musician known by his stage name Dr. Alban, and the late Gogo Nwakochi, a successful businessman and husband of the late famous novelist Flora Nwakoba.

Princess Tricia Nobani

Princess Tricia NobaniIgbo society is very selective. Applicants must own property, have verifiable income, be married or married, and maintain an impeccable reputation.

Descendants of slaves, known as oho, are not allowed to join. These are people whose ancestors were owned by others, either by war or purchase – remnants of a social order that some are now working to abolish.

“We now say it is time to get rid of this hateful, outdated and useless system, so that we can be one,” said Udenyi Nduka, a former Igbo secretary and spokesman for the king.

“If you go to America, some of our children are married to black Americans, even some Ogbuagu. These black Americans are products of the same system, so what is the problem at home?”

He explained that the traditional process of abolishing the Oho system had already begun, with consultations taking place among families who previously owned slaves. This is expected to lead to the enactment of traditional rituals that will formally declare their freedom from oho status.

“Once this is done, the Igbo will call a meeting and start accepting them,” Nduka said.

Despite its status, some criticize the Igbo, claiming that it only benefits the egos of its members.

At every gala I attended, there was at least one person in the crowd grumbling about how the thousands of dollars spent could be better used to develop the city or fund scholarships.

Princess Tricia Nobani

Princess Tricia NobaniBut Anish disagrees and says: “Igbo is not a society you come to to achieve; it is a society you come to because you have already achieved.

“The Ogbuagu have brought more development to Oguta than others. They are the largest employers of labour.”

Mr. Anish also pointed out that the money spent on banquets and other celebration requirements goes back into the local economy.

Today, the Igbo Association's membership is spread throughout the world, with nearly half of its members residing in the diaspora. However, whether in Europe or the United States, Ojota men remain deeply connected to their roots.

“I come back about three times every year because I love the Oguta tradition,” Adesua said. “With all the stress I have in the diaspora, I love coming back home to relax.”

For Mr. Okoroafor, the journey from a young boy dreaming of hunting cheetah to respected Ogbuajo has been worth the wait.

“Ogota is a beautiful city with many people who have excelled in different fields,” he said, his voice full of pride.

“The last time I went home was in 2016, but now that I am from Ogbuaju, I will be returning home more regularly.”

Adobe Tricia Nubane is a Nigerian freelance journalist and novelist based in Abuja and London.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC