Bald

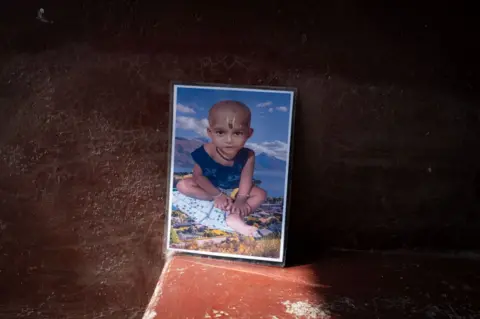

BaldYou will never forget Mangala Pradan that morning when she lost her one -year -old son.

This happened 16 years ago, in the harsh Sondiga region, a vast and harsh delta that includes 100 islands in the West Bengal state, India. Her son Ajet, who just started walking, was full of life: fun, troubled, and curious about the world.

That morning, like many others, the family was busy with its daily work. Mangala f unders the breakfast and took it to the kitchen while it was cooking. Her husband abroad was buying vegetables, and her sick mother -in -law rest in another room.

But Ajit Al -Saghir, who was always keen to explore, fled without anyone noticing. Mangalla shouted, asking her mother -in -law to monitor him, but there was no response. A few minutes later, when I realized the calm of the situation, the panic prevailed.

“Where is my son? Did someone see my son?” I shouted. The neighbors rushed to help.

And the despair soon turned into a sorrow when its son -in -law found the small Ajit body floating in the pond. The annihilation is outside their dilapidated house. The little child wandered and slipped into the water – and the moment of innocence turned into an unimaginable tragedy.

Bald

BaldToday, Manga is one of the 16 mother in the region walking or riding the bike to two temporary cities established by a non -profit organization where they take care of, feed and teach about 40 children, whose parents are delivered on their way to work. “These mothers are the rituals of children who are not their children,” says Sujoy Roy of the Cini Institute (CINI), who created the nursery.

The need for such care is an urgent matter: countless children are still drowning in this river area full of ponds and rivers. In every house there is a pool used for bathing, washing, and even dragging drinking water.

A survey conducted by the George Institute and CINI in 2020 found that nearly three children are between one year and nine years old, drowning daily in the Sondarbnce area. Drowning was climax in July, when seasonal rain began, and between ten in the morning and second in the afternoon. Most of the children were not subject to control at the time as care providers were busy with household chores. About 65% of them drowned at a distance of 50 meters from their homes, and only 6% received care from licensed doctors. Health care was in a state of chaos: Hospitals were rare and many public health clinics have stopped working.

Bald

BaldIn response, the villagers clung to the old myths to save the children who were rescued. They rotated the child's body over the head of an adult while chanting the supplications. They hit water with sticks to expel lives.

“As a mother, I know the pain caused by a child's loss,” Manga told me. “I don't want any other mother to bear what she did. I want to protect these children from drowning. We live among many risks anyway.”

Life in Sondapeans, which is inhabited by four million people, is a daily conflict.

The tigers, known for attacking humans, wander seriously near the crowded villages and entering them where the poor live Those who live, often sit on the ground.

People hunt fish, collect honey, and collect cancers under the constant threat of toxic tigers and snakes. From July to October, rivers and ponds are filled with heavy rains, hurricanes hit the area, and the raging waters swallowed villages. Climate change exacerbates this uncertainty. Nearly 16 % of the population here ranges between one year and nine years.

Bald

Bald“We have always coexisted with water, unaware of risks, until the tragedy occurred,” says Sujata Das.

Sogata's life turned three months ago when her 18 -month -old daughter, Ambika, sank in a pool in the joint family home in Coltieli.

Her children were attending training lessons, some family members went to the market, and her elderly aunt was busy working at home. Her husband, who usually worked in the southern state of Kerala, was at his home that day, as he was repairing a fishing network in the nearby fishing vessel. Sujata went to bring water from a local manual pump because the delivery of the promised water in her home has not yet been achieved.

“Then we found it floating in the blessing. The rain fell and the water rose. We took it to a local Antichrist, who declared her death. This tragedy has woke us what we should do to prevent such tragedies in the future.” Sugata says.

Bald

BaldSujata, like others in the village, plans to fold its blessing with bamboo and nets to prevent children from wandering in the water. She hopes that children who do not know swimming will be taught in the village pools. She wants to encourage neighbors to learn cardiovascular resuscitation to provide life -saving help to children who have been rescued from drowning.

“Children do not vote, so the political will to address these issues is often not present,” says Mr. Roy. “That is why we focus on building local ability to withstand and spread knowledge.”

Over the past two years, about 2000 villagers have received training in the cardiovascular resuscitation. Last July, a village saved a child who was drowning by reviving him before being transferred to the hospital. He adds: “The real challenge lies in creating custody houses and raising awareness among members of society.”

The implementation of even simple solutions is a challenge due to local costs and beliefs.

Bald

Bald Bald

BaldIn the Sondapens area, the myths related to the anger of the water gods made it difficult to persuade people to fold their pools. In the neighboring Bangladesh, as drowning is the main cause of the death of children between the ages of a year and four, a wooden children's kindergarten was inserted into the squares to maintain the safety of children. However, compliance was low – as children hated it, and the villagers often used it to raise goats and ducks. “This has created a false feeling of safety, and the drowning rates have increased slightly over a period of three years,” says Jagnor Jagnor, an epidemic of injuries at the George Institute.

Ultimately, non -profit organizations established 2,500 nurseries in Bangladesh, reducing drowning deaths by 88%. In 2024, the government expanded this number to 8,000 centers, benefiting from 200,000 children annually. Water -rich Vietnam focused on children between six and ten years old, using contracts from death data to develop policies and teach survival skills. This led to a decrease in drowning rates, especially among school children traveling through waterways.

Bald

Bald Bald

BaldDrowning still represents a major global problem. In 2021, an estimated 300,000 people were drowned, or more than 30 people died every hour, according to the World Health Organization. Nearly half of them were under the age of 29, and the quarter is under the age of five. India's data is meager, as it officially recorded about 38,000 deaths in 2022, although the actual number is much higher than that.

In the Sondarbnce region, the cruel reality is always present. For years, children were allowed to roam freely or tie them with ropes and fabric to prevent them from wandering. The great anklets were used to alert parents to the movements of their children, but in these harsh landscapes and water surrounding, there is nothing really safe.

Six -year -old son Kakuli Das entered a surplus pond last summer while handing a piece of paper to a neighbors. Ishhan drowned because of his inability to distinguish between the road and water. He suffered from episodes when he was a child and was unable to learn to swim because of the risk of fever.

“Please, beg to every mother: make your blessing, learn how to revive children and teach them how to swim. It is about saving lives. We cannot wait,” says Kaccouli.

Currently, the nurseries are considered a beacon for hope, as it provides a way to maintain children's safety from water risks. In the afternoon recently, the four -year -old Manic Pal sang a delightful song to remind his friends: I will not go to the blessing alone / unless my parents are with me / I will learn to swim and stay standing on his feet / and I live my life free of fear