BBC

BBCEleven years ago, I left Damascus without knowing whether I would return or not.

At that time, the city was in the grip of war. The capital has been engulfed in intense violence, following President Bashar al-Assad's brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests. At any moment you can To be shot dead in the streets.

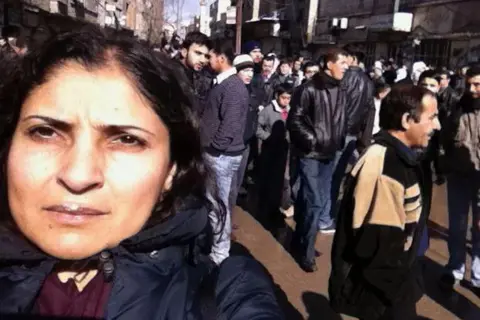

I covered for the BBC from inside Syria the first protests in 2011 “Day of Wrath”Then shootings, killings, disappearances, air strikes, explosive barrels – until I became numb and lost hope.

I was arrested several times. The regime restricted my movements and threatened me, and in 2013 I had to leave.

For the past decade, I have lived in a spiral of hope and despair, watching my country being torn apart from the outside. Death, destruction and arrest. Millions flee and become refugees.

Like many Syrians, I felt as if the world had forgotten our country. There was no light at the end of the tunnel.

When people took to the streets at that time to demand the overthrow of the regime, I never imagined it would actually happen, given President Assad's strong supporters in Russia and Iran.

But on Sunday, in the blink of an eye, everything changed.

Last week, I was in Beirut covering the fall of Aleppo and Hama to anti-Assad militants, but I didn't really think it would lead to change. I thought Syria would split in two, with Damascus and the coastal cities remaining in Assad's hands.

After midnight on Saturday, things suddenly took a turn. By 04:00, the fall of the regime and the departure of Assad was announced. As I write these words now, I still can't believe this is true.

Over the weekend I was trying to get a permit to enter the country from one of the most feared secret police organizations in Syria, called the Palestine Branch. They had an arrest warrant in my name, because of my coverage of the protests.

I cannot forget my arrest during the first week of the 2011 uprising. I saw men lining up to be beaten, fresh blood on the ground, and screams of torture. A security officer grabbed my mouth and said he would “cut it out for me” if I said a word.

On Sunday, I rushed with my colleagues to the Syrian border. Now there is no one left in the Palestine Branch, neither the security officers nor the investigator who threatened me when I last tried to enter Syria in January. He told me he could bury me seven stories underground without anyone knowing. I wondered where he was now. How did he feel about the thousands he interrogated and threatened? Or those who were tortured to death in Assad's prisons?

She crossed the border into Syria without fear of arrest. When I went on air for the BBC from Damascus, I covered without fear for my safety.

An atmosphere of joy prevails in Damascus despite fears Islamist rebels take control And whether they will ensure safety in the country. Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham fighters then protected public institutions from looting The mob stormed the presidential palaceAnd the prisoners were released.

A group from Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham met with Christian residents in Bab Touma, a neighborhood in Damascus, to offer assurances that they were not seeking to limit their freedoms.

Some in the Alawite community – who have long supported Assad – are concerned about what will happen to them, but so far there have been no reports of sectarian violence.

Since Sunday, friends and family members who fled have been texting me saying they will be back. It seems like everyone wants to go home.

My apartment in central Damascus was destroyed in 2013 when I left, after the authorities deemed me a traitor and banned me from living there. Security forces and local officials stormed the building and destroyed its walls and ceilings.

Last month, she was able to regain his ownership after paying thousands of dollars in bribes. It will take some time to rebuild it, but that's what I'll do.

Perhaps when Syria is ready, it will be ready for all of us to return.