Eve Blouin

Eve Blouin“I know that it is possible to die twice,” screenwriter Eve Blouin says in an afterword at the end of her mother's autobiography. “First comes the physical death… and forgetfulness is the second death.”

Eve understands this feeling more than anyone else.

In the 1950s and 1960s, her mother, the late André Blouin, threw herself into the struggle for a free Africa, mobilizing DRC women against colonialism and rising to become a key advisor to Patrice Lumumba, the DRC's first prime minister and a revered independence hero.

She has shared her ideas with famous revolutionaries such as Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Sékou Touré in Guinea, and Ahmed Ben Bella in Algeria, but her story is barely known.

In an effort to address this injustice, Blouin's memoir, My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, is being reissued after spending decades out of print.

In the book, Blouin explained that her longing for decolonization was caused by a personal tragedy.

It originated between the Central African Republic and Congo Brazzaville, which at the time were French colonies called Ubangi-Shari and French Congo respectively.

In the 1940s, her two-year-old son Rene was being treated in hospital for malaria in the Central African Republic.

Rene was mixed race Like his mother, because he is a quarter African, he was denied medication. Weeks later, Rene died.

“My son’s death politicized me like nothing else,” Blouin wrote in her memoir.

She added that colonialism “was no longer a question of my fate, but rather an evil system whose tentacles reached every stage of African life.”

Blouin was born in 1921 to a 40-year-old white French father and a 14-year-old black mother from the Central African Republic.

The two met when Blouin's father passed by her mother's village to sell goods.

“Even today, the story of my father and mother, even though it caused me so much pain, still amazes me,” Blouin said.

When she was only three years old, Blouin's father placed her in a mixed-race monastery Girls, which was run by French nuns in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville.

This was it A common practice in the African colonies of France and Belgium – It is believed that thousands of children born to colonists and African women were sent to orphanages and separated from the rest of society.

“The orphanage served as a kind of dustbin for the waste of this black-and-white society: children of mixed blood who did not fit anywhere,” Blouin wrote.

Eve Blouin

Eve BlouinBlouin's experience at the orphanage was extremely negative – she wrote that children at the institution were subjected to whippings, lack of nutrition, and verbal abuse.

But she was stubborn. She ran away from the orphanage when she was fifteen after the nuns tried to force her to marry.

Blouin eventually married twice of her own free will. After René's death, she moved with her second husband to Guinea, a country in West Africa that was also under French rule.

Guinea was at the time in the middle of a “political storm,” she wrote. France had promised the country its independence, but also asked Guineans to vote in a referendum on whether or not the country should maintain economic, diplomatic and military relations with France.

The Guinean branch of the pan-Africanist movement, the African Democratic Rally (RDA), wanted the country to vote no, arguing that the country needed full liberalization. In 1958, Blouin joined the campaign, driving around the country to speak at rallies.

A year later, Guinea gained independence through a “no” vote, and Sékou Touré, leader of the Guinean Democratic Rally, became the country's first president.

At this point, Blouin began to develop significant influence in postcolonial Pan-African circles. After Guinea's independence, she wrote, she used this influence to advise the new president of the Central African Republic, Barthelemy Buganda, and persuade him to step down in a diplomatic spat with Congo-Brazzaville's post-independence leader, Fulbert Yulu.

But advice was not all that Blouin had to offer a rapidly changing Africa.

In a restaurant in Conakry, the capital of Guinea, she met a group of liberation activists from what later became the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They urged her to help them mobilize Congolese women in the war against Belgian colonial rule.

Blouin was pulled in two directions. On the one hand, she had three young children – including Eve – to raise. On the other hand, Eve, now 67, told the BBC: “She had perfectionist anxiety and a certain anger at the world as it was.”

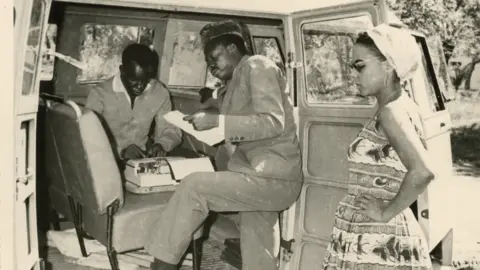

In 1960, with Nkrumah's encouragement, Andre Blouin flew alone to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. She joined prominent male liberation activists, such as Pierre Molili and Antoine Gizinga, on the road, campaigning across the country's 2.4 million square kilometers (906,000 sq mi). She was a striking figure, moving through the jungle with her hair styled, tight dresses and elegant sheer shades.

Eve Blouin

Eve BlouinIn Kahimba, near the border with Angola, Blouin and her team paused their campaign to help build a base for Angolan independence fighters who had fled Portuguese colonial authorities.

She addressed crowds of women, encouraging them to push for gender equality as well as for Congolese independence. She also had a talent for organization and strategy.

Colonial powers and the international press soon learned of Blouin's work. They accused her of being, among other things, Nkrumah's mistress, Sekou Touré's agent, and “the courtesan of all African heads of state.”

She attracted more attention when she met Lumumba.

In her book, Blouin describes him as a “graceful and elegant” man whose name “was written in golden letters in the Congolese sky.”

When the country gained independence in 1960, Lumumba became its first prime minister. He was only 34 years old.

Lumumba chose Blouin to be his “chief of protocol” and speechwriter. The duo worked together so closely that the press dubbed them “Lumum-Blouin”.

The American magazine Time described Blouin as a “handsome 41-year-old” with “a steely will and quick energy that make her an invaluable political aid.”

But a series of disasters struck Lomum Plouin's team – and the newly formed government – just days into their term.

First, the army revolted against its white Belgian commanders, sparking violence across the country. Subsequently, Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States supported secession in Katanga, a mineral-rich region in which all three Western countries had interests. Belgian paratroopers returned to the country, ostensibly to restore security.

Blouin described the events as a “war of nerves” in which “traitors are organizing everywhere.”

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissShe wrote that Lumumba was “the true modern-day hero,” but also admitted that she thought he was naive and, at times, too soft.

“It is true that those of the best faith are often the most cruelly deceived,” she said.

Within seven months of Lumumba taking charge, Army Chief of Staff Joseph Mobutu seized power.

On January 17, Lumumba was shot to death, with the tacit support of Belgium. It is possible that the UK is complicitWhile the United States had previously organized plots to kill Lumumba, fearing his sympathies with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Blouin said in her book that the shock and grief caused by Lumumba's death left her speechless.

“I've never been left without a torrent of things to say,” she wrote.

She was living in Paris at the time of the killing, having been forced into exile after Mobutu's coup.

To ensure that Blouin would not speak to the international press, the authorities forced her family – who had moved to Congo – to remain in the country as “hostages”.

The breakup was traumatic for Blouin, who, as Eve describes, was “very protective” and “very motherly.”

Reflecting on her mother's character, Eve adds: “No one wants to antagonize her, because even though she has a big and generous heart, she can be a bit fickle.”

While Blouin was in exile, soldiers ransacked her family home and brutally pistol-whipped her mother, permanently damaging her spine.

The Blouin family was finally able to join her after months of separation.

They spent a brief period in Algeria – where the country's first post-independence president, Ahmed Ben Bella, offered them refuge.

Then they settled in Paris. Blouin remained involved in Pan-Africanism from afar “in the form of articles and almost daily meetings,” as Eve writes in the memoir’s afterword.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissWhen Blouin began writing her autobiography in the 1970s, she still had great respect for the independence movements to which she had devoted herself.

She praised Sékou Touré, who by then had established a one-party state and was ruthlessly suppressing freedom of expression.

But Blouin felt desperate because Africa had not become as “free” as she had hoped.

“It is not outsiders who have harmed Africa more than others,” she wrote, “but rather the distorted will of the people and the selfishness of some of our leaders.”

She was saddened by the death of her dream, to the point that she refused to take the cancer medication that was destroying her body.

“It was horrible to watch. I was completely helpless,” Eve said.

Blouin died in Paris on April 9, 1986, at the age of 65. According to Eve, the world greeted her mother's death with “grim indifference.”

However, it is still an inspiration in some corners. In Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, there is a cultural center named after Plouin that offers the likes of educational programmes, conferences and film screenings – all underpinned by the spirit of Pan-Africanism.

And through My Country Africa, Blouin's extraordinary story is being released for the second time, this time in a world showing greater interest in women's historical contributions.

New readers will learn about the girl who went from being hidden by the colonial system, to fighting for the freedom of millions of black Africans.

My Country, Africa: The Autobiography of Black Passionaria, published by Verso Books, goes on sale January 7 in the UK.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC