Climate and Science Reporter

Data journalist

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe world's largest iceberg has crashed onto a remote British island, potentially endangering penguins and seals.

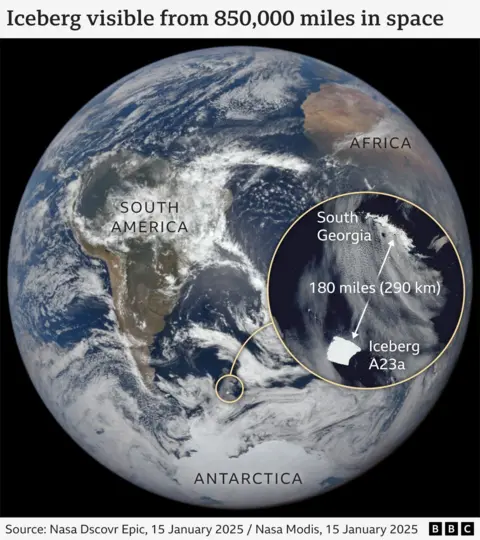

The iceberg is rotating north from Antarctica towards South Georgia, a rugged British region and wildlife refuge, where it could collapse and break apart. It is currently 173 miles (280 km) away.

Countless birds and seals died on the icy bays and beaches of South Georgia when past giant icebergs prevented them from feeding.

“Icebergs are inherently dangerous. I would be very happy if they completely missed us,” Navy Captain Simon Wallace told BBC News, speaking from the South Georgia government ship Pharos.

BFSAY

BFSAYAround the world, a group of scientists, sailors and fishermen are eagerly examining satellite images to monitor the daily movements of this queen of icebergs.

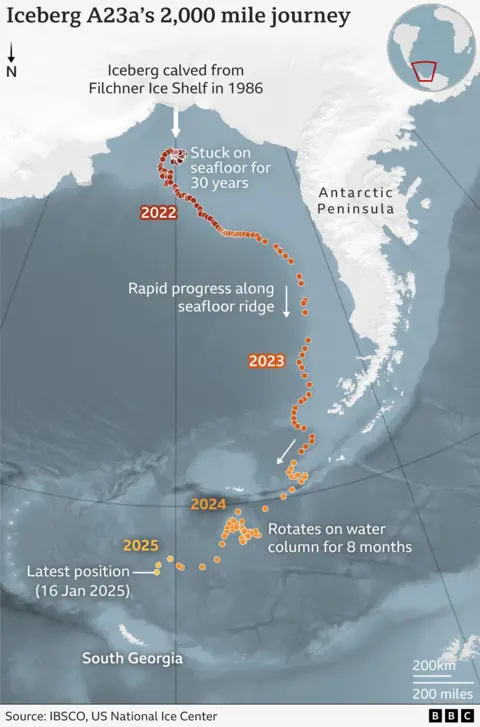

that it Known as A23a It is one of the oldest in the world.

It broke off, or broke off, from the Filchner Ice Shelf in Antarctica in 1986 but became stuck on the seafloor and then trapped in the ocean gyre.

Finally, in December, she was freed and is now on her final journey, speeding into oblivion.

North Antarctica's warm waters are melting and weakening its vast cliffs, which reach 1,312 feet (400 metres) high, taller than the Shard in London.

Its area was once 3,900 square kilometers, but the latest satellite images show it is slowly disintegrating. It now has an area of about 3,500 square kilometres, roughly the size of the English county of Cornwall.

Large slabs of ice break off and sink into the water around their edges.

A23a could split into vast fragments on any given day, which may remain there for years, like floating ice cities wandering uncontrollably around South Georgia.

This is not the first massive iceberg to threaten the South Georgia and Sandwich Islands.

In 2004, one of these animals, called A38, settled on the continental shelf, leaving penguin chicks and seal pups dead on beaches, where huge chunks of ice blocked their access to feeding grounds.

The area is home to valuable colonies of king emperor penguins and millions of elephants and fur seals.

“South Georgia is located in an alley of icebergs, so impacts on fisheries and wildlife, both of which have great resilience, are expected,” says Mark Belcher, a marine ecologist who advises the South Georgia government.

Sailors and fishermen say icebergs are a growing problem. In 2023, a device called the A76 scared them when it nearly stopped working.

“Parts of it were pointing upwards, so it looked like great ice towers, or an ice city on the horizon,” says Belcher, who saw the iceberg while at sea.

These panels still remain around the islands today.

“It's bits from the size of several Wembley stadiums to pieces the size of your office,” says Andrew Newman of Argus Froyannis, a fishing company that operates in South Georgia.

“These pieces basically cover the island, and we have to make our way across them,” says Captain Wallace.

Sailors on board his ship must be constantly vigilant. “We have searchlights on all night to try to see the ice, it can come out of nowhere,” he explains.

The A76 has been a “game changer”, according to Mr Newman, having “a huge impact on our operations and on maintaining the safety of our ship and crew”.

Simon Wallace

Simon WallaceThe three men describe a rapidly changing environment, with glaciers clearly retreating from year to year, and fluctuating levels of sea ice.

Climate change is unlikely to have been behind the birth of A23a because it separated a long time ago, before many of the effects of rising temperatures we are seeing now.

But giant icebergs are part of our future. As Antarctica becomes more unstable as ocean and air temperatures rise, larger pieces of ice sheets will break off.

Before his time was up, A23a left a parting gift for the scientists.

A team from the British Antarctic Survey aboard the research ship Sir David Attenborough found themselves near A23a in 2023.

Scientists were quick to seize this rare opportunity to study what huge icebergs are doing to the environment.

Tony Joliffe/BBC

Tony Joliffe/BBCThe ship sailed into a crack in the iceberg's giant walls, and doctoral researcher Laura Taylor collected precious water samples 400 meters from the iceberg's slopes.

“I saw a huge wall of ice that was way above me, as far as I could see. It had different colors in different places. Chunks were falling — it was absolutely amazing,” she explained from her lab in Cambridge where she now works. Sample analysis.

Her work investigates the effect of meltwater on the carbon cycle in the Southern Ocean.

Getty Images

Getty Images“This isn't just water we drink,” says Ms Taylor. “It's full of nutrients and chemicals, as well as small animals like phytoplankton frozen inside.”

When it melts, the iceberg releases these elements into the water, changing the physics and chemistry of the ocean.

This could lead to more carbon being stored deep in the ocean, where molecules sink from the surface. This would of course prevent some of the planet's carbon dioxide emissions that contribute to climate change.

Icebergs are notoriously unpredictable and no one knows exactly what they will do next.

But soon the giant, looming over the islands, will appear as large as the region itself.