BBC

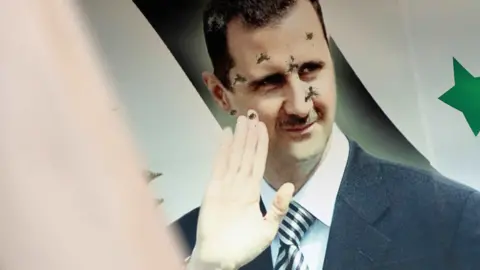

BBCIn downtown Aleppo, a huge billboard in the main square bearing a picture of President Bashar al-Assad, which was a feature of any Syrian town and village, was burned and then removed.

The red, white and black national flags that adorned the lampposts were also removed and replaced with what is known as the “Independence Flag.” On the road, outside the city hall, a giant banner bearing a picture of a lion had been removed; Another had his face riddled with bullets, and for whatever reason he was kept there.

Across Aleppo, residents and the new authorities seemed keen to get rid of anything symbolizing the Assad family – Bashar came to power in 2000 after the death of his father, Hafez, who ruled for 29 years.

I first came to Aleppo as a student in 2008, and banners bearing the lion’s face were prominent in public squares, streets and government buildings; All appear to have been removed or destroyed.

It was the first major city captured by the Islamist-led rebels earlier this month, in their stunning offensive that ousted Assad and brought freedom to this country after five decades of oppression — at least for now.

One of the first things they did was take down a large equestrian statue of the former president The late brother Basil; A statue of Hafez was also vandalized.

Aleppo, once a bustling commercial centre, saw fierce battles between opposition fighters and government forces during the civil war, which began in 2011, when Assad brutally suppressed peaceful protests against him.

Thousands were killed. Tens of thousands more fled.

Now that Assad is gone… Many are returning from other parts of Syria and even from abroad.

Early in the war, eastern Aleppo, a rebel stronghold, was surrounded by pro-regime forces and came under intense Russian bombing. In 2016, It was regained by government forces, a victory considered at the time to be a turning point in the conflict.

To this day, the buildings remain destroyed, with piles of rubble waiting to be collected. The return of Assad's forces means that it has been too dangerous for those who fled to return – until now.

Mahmoud Ali (80 years old) said, “When the regime fell, we could raise our heads.” He left when fighting there intensified in 2012. He moved with his family to Idlib, in the northwest of the country, which, until two weeks ago, was a rebel enclave in Syria, run by Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham. The group that led the attack on Assad.

“Oppression is what I say all my life in the hands of the Assad family. Anyone who demands any rights will be sent to prison. We protested because there was a lot of oppression, especially on us poor people.”

His 45-year-old daughter, Samar, is one of millions in Syria who have only known that the country is ruled by the Assad family.

“Until then, no one dared to speak out because of the regime’s terrorism,” she said.

“Our children were deprived of everything. They did not have a childhood.”

It is striking that these sentiments were shared so freely in a country where dissent is not tolerated; The secret police, known as the Mukhabarat, seemed to be omnipresent and spying on everyone, and critics disappeared or were sent to prison, where they were tortured and killed.

Across Aleppo, the new authorities have installed billboards bearing images of chains around wrists that say: “The release of detainees is a debt on our necks.”

“We are happy, but there is still fear,” Samar said. “Why are we still afraid? Why is our happiness not complete? Because of the fear they (the regime) instilled in us.”

Her brother Ahmed agreed. “You could be sent to prison for saying simple things. I'm happy, but I'm still worried. But we won't live under oppression again.”

His father intervened to agree with him. “It's impossible.”

The family lived in a small apartment, where there was intermittent electricity and no heating.

Now that they are back, they don't know what to do, like many others here. It is estimated that more than 90% of Syria's population lives in poverty, and there are broader concerns about how Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham is killing it. Which began as a branch of Al QaedaHe will run the country.

A woman who lives in a nearby apartment said: “No one can take away my happiness. I still can't believe we are back. May God protect those who took back the country.”

In the main square, a man said to me: “I really hope we do it right, and there will be no return to violence and repression.”

In Mahmoud Ali's apartment, the “independence flag” with its four red stars in the middle was drawn on white paper and placed on the coffee table in the living room.

“We still cannot believe that Assad is gone,” Samar, one of his daughters, told me.