BBC

BBCWhen Mzwandile Makwai was lowered into a South African mine into a red metal cage attached to an above-ground crane, the first thing that struck him was the smell.

He told the BBC: “Let me tell you something, those bodies smelled really bad.”

When he returned home later that day, he told his wife that he could not eat the meat she had cooked.

“This is because when I spoke to the miners, they told me that some of them had to eat other (people) inside the mine because there was no way they could find food. They were eating cockroaches too,” he said in a phone call. From his house.

Allegations that the miners resorted to eating human flesh to survive were also mentioned by other miners rescued in December, in statements submitted to the High Court.

Makwai, an ex-convict, known locally as Shasha, lived in the town of Khoma which was close to the abandoned mine at Stilfontein. The 36-year-old, who spent seven years in prison for theft, volunteered to come down to help in the rescue efforts.

“I am being rehabilitated by correctional services and I volunteered because people in our community were asking for help for their children and siblings.

“The rescue company said they didn’t have anyone who wanted to come down. So my friend Mandla and I agreed to volunteer so we could help our brothers surface and retrieve the bodies.”

But despite his desire to help, the 25-minute journey through the 2 km (1.2 mile) deep gorge filled him with terror.

Agence France-Presse

Agence France-PresseSometimes the crane stopped and moved, leaving him hanging in the dark. Once he descended into the mine, he was shocked by what he saw.

“There were a lot of bodies, more than 70, and about 200 or so people suffering from dehydration.

“I felt very weak when I saw them, it was painful to see them. But Mandla and I decided that we needed to be strong and not show them how we feel so that we could motivate them.”

This story contains video that some may find distressing.

The miners, who had waited for help for months, were given a hero's welcome.

“They were very happy,” he says.

The miners were stuck there following a nationwide police operation to end illegal mining at abandoned sites that had been closed down, as the industry – once the backbone of the country's economy – was shrinking.

It is no longer profitable for multinational mining companies to operate in many places, but the promise of continuing to find gold deposits has been a magnet for many desperate people – especially illegal immigrants.

Thousands of columns were abandoned.

In November, police intensified their efforts at the Bavelsfontein mine in Stilfontein, cordoning off the mine entrance and refusing to allow food and water to reach them.

Before the rescue operation began on Monday, the local community tried to take matters into their own hands by lowering a rope down the shaft to try to pull some of the men out.

They also sent letters and told the miners that help was coming.

“So when we got there, they were already waiting for the crane. Now when they see us, they see us as their bosses, their messiahs: the people who came from the outside into the pit to help them emerge again.”

Police say illegal miners have always been able to venture out on their own but have refused to do so because they fear arrest. But McQuay disagrees: “It's a lie that people didn't want to come out. These people were desperate for help, and they were dying.”

While at the mine site on Tuesday, the BBC saw dozens of men rescued.

They looked emaciated, and their bones were visible through their clothes. Some of them could barely walk and had to be helped by medical staff.

In affidavits submitted to the Supreme Court, illegal miners describe in minute detail the slow and painful deaths of their peers. They say that many died of hunger.

“From September to October 2024, the absence of even basic livelihoods was absolute, and survival became a daily battle against famine,” one miner said.

McQuay says the men he rescued were so weak that a rescue cage designed to hold only seven healthy adults could hold 13 of them.

“They were severely dehydrated and had lost some weight, so we were able to put more in the cage, because they would not have been able to survive another two days in the hole. They would have died if we didn't get them out as soon as possible.” “.

Volunteers were also responsible for removing the bodies.

He added, “The rescue services gave us bags and asked us to put the bodies in them and lift them into the cage, which we did with the help of some miners.”

The rescue operation was initially supposed to last at least a week, but after just three days, volunteers said there was no one left underground.

Authorities sent a camera down the shaft to conduct the final sweep. They say the mine will now be closed permanently.

But this experience deeply affected McQuay.

At one point during the call, he asked to repeat a question, explaining that his hearing had been affected since going down the mine, perhaps due to stress.

But the most difficult impact was from what he witnessed.

“I have to tell you I'm traumatized. I'll never forget seeing these people for the rest of my life.”

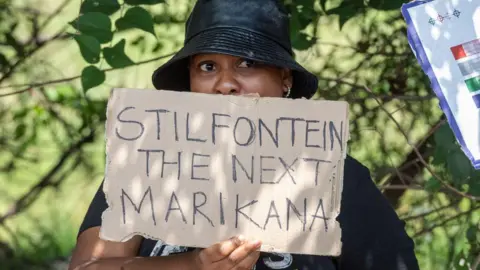

For activists and trade unions helping the community, the killing of 87 people at the mine amounts to a “massacre” committed by the authorities.

The use of the word emotional has drawn comparisons with the word Police shot dead 34 striking miners in Marikanaabout 150 kilometers (93 mi) from Stilfontein, in 2012.

But this time no triggers were pulled. Instead it appears that many of the men starved to death.

The authorities reject the idea of their responsibility.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government began a crackdown on illegal mining in December 2023 through Operation Fala Umjodi (meaning “close the pit” in IsiZulu).

Gangs, often led by former employees, have taken over abandoned mines and sold what they find on the black market.

People have been lured to participate in this illegal trade, either forcefully or voluntarily, and forced to spend months underground prospecting for minerals. The government says illegal mining has cost South Africa's economy $3.2bn (£2.6bn) in 2024 alone.

As part of the police operation, entry points into several abandoned mines were closed, along with food and water supplies, in an attempt to flush out the illegal miners, known locally as zama zamas (which translates as “seize the moment”).

While Vala Umjodi has had great success in other provinces, the old gold mine in Paffalfontein presents a unique challenge.

Before the police operation, most miners could only access the underground through a makeshift pulley system operated by people on the surface.

But they then abandoned the top of the mine shaft when security officials arrived in droves in August, leaving those in the mine stranded.

Community members then stepped in to help, pulling a few people out using ropes, but this was a long and arduous process.

There were other difficult and dangerous exits, and approximately 2,000 people turned up – most of whom were arrested and remain in police custody.

It is not clear why the others did not get out – they may have been too weak or threatened by gang members in the mine – but were left in desperate circumstances.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPolice said on Thursday that only two of the 87 people who died had been identified, explaining that the fact that many of them were illegal immigrants made the process more difficult.

“We see that the government has blood on its hands,” Magnificent Mendebele, of the United Action Group for Mining Affected Communities (MACOA), told the BBC.

He said the miners received no warning about what was about to happen before the police operation began.

Over the past two months, Makwa has been at the forefront of various court battles launched to force the government to first authorize the supplies and then undertake the rescue operation.

Blaming the government reflects previous statements from families who said authorities killed their loved ones.

They have taken a hard line since the intensification of the operation. In November, one of the ministers, Khumbudzo Ntshavheni, made the infamous remark during a press conference that they would “fizzle them out.”

The state refused to allow food or anyone to help reclaim the miners, and only gave in after several successful court applications.

In November, small quantities of instant corn and water reached the bottom of the well, but in a statement to the court, one miner said it was not enough for the hundreds of men at the bottom, many of whom were too weak to chew and swallow. they.

More food was delivered in December, but again was unable to support the men.

Given that the operation to bring in the men and bodies lasted only three days, what is difficult for Mr. Mendebele to understand is why this could not have been done sooner, when it was clear that there was a problem.

“Frankly, we are disappointed in our government that this assistance has come so late.”

While the government has yet to officially respond to the accusations, police have pledged to continue broader operations to clear abandoned mines in the country until May this year.

Speaking to reporters in Stilfontein on Tuesday, Mining Minister Gwede Mantashe did not apologise. He said the government would intensify its campaign against illegal mining, which he described as a crime and an “attack on the economy.”

On Thursday, Police Minister Senzo Mchunu was a bit more conciliatory.

“I understand and accept that this is an emotional issue. Everyone wants to make judgments… but it would help all of us as South Africans to wait until the pathologists finish and complete their work,” he said.

The police defended their actions, saying that providing the miners with food would have “allowed crime to flourish.”

Illegal miners have been accused of promoting crime in the communities in which they work.

A number of stories have been published in local media linking Zama Zama to various rapes and murders.

But for McQuay, who put his safety on the line to help the miners, the men at the Stilfontein mine were just trying to make a living.

“People descended two kilometers with ropes and risked their lives to provide food for their families.”

He said he wants the government to grant licenses to artisanal miners who are forced to go into abandoned mines due to the high unemployment rate in South Africa.

“If your children are hungry, you won't think twice about going there because you have to feed them. You will be risking your life to put food on the table.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC