Mike Wendling/BBC News

Mike Wendling/BBC NewsWith light snow falling outside, worshipers gathered at Lincoln United Methodist Church in Chicago to pray and plan for what will happen when Donald Trump takes office next week, when the president-elect has promised to begin the largest expulsion of illegal immigrants in U.S. history.

“January 20 will come before we know it,” Pastor Tania Lozano Washington told the congregation after handing out cups of Mexican hot chocolate and coffee to warm the crowd of about 60 people.

The church is located in Pilsen, a predominantly Latino neighborhood, and has long been a hub for pro-immigration activists in the city's large Hispanic community. But Sunday services are now in English only, as in-person Spanish language services have been cancelled.

The decision was made to move them online due to concerns that these gatherings could be targeted by anti-immigration activists or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The next president has said he will deport millions of illegal immigrants, threatened workplace raids, and reports suggest he may do so. Get rid of the long-standing policy that made churches off-limits to ICE arrests.

According to one parishioner, David Crusino, who was born in the United States, “The threat is very real. It is very alive.”

Cruzino said his mother entered the country illegally from Mexico but has been working and paying taxes in the United States for 30 years.

“With the new administration coming in, it became more like persecution,” he told the BBC. “I feel like we are being unfairly discriminated against and targeted, even though we cooperate (with) this country endlessly.”

But across the country, more than 1,400 miles (2,253 kilometers) to the south in Texas' Rio Grande Valley, another mostly immigrant community has a very different view of the impending inauguration — a sign of how starkly divided Latino communities are. On illegal immigration and Trump. Trump's approach to the US-Mexico border.

“Migration is necessary… but it is the right way,” said resident David Boras, a farmer and botanist.

“But with Trump, we're going to do it right.”

The area is separated from Mexico only by dark, shallow, narrow river waters and patches of dense vegetation and mesquite – and locals say the reality of daily life on the border has increasingly opened their eyes to what many see. Such as the risks of illegal immigration.

“I've had (immigrant) families knock on my back door, asking for water and shelter,” said Amanda Garcia, a resident of Starr County, where nearly 97% of residents identify as Latino. In the United States outside of Puerto Rico.

“We had an incident where a young lady was alone with two men, and you could see she was tired – and being abused.”

Bernd Debusmann Jr/BBC News

Bernd Debusmann Jr/BBC NewsOver the course of dozens of interviews in two of the counties that make up the Rio Grande Valley — Starr and neighboring Hidalgo — residents described a series of other border-related incidents, ranging from waking up to migrants on their property to seeing busts of cartel hideouts used in drug smuggling. Or dangerous high-speed chases between authorities and smugglers.

Many in the predominantly Latino part of Texas are immigrants themselves, or are children or grandchildren of immigrants. Once a reliable Democratic stronghold in “red” Texas, Starr County swung to Trump in the 2024 election — the first time Republicans had won the county in more than 130 years.

Nationally, Trump received about 45% of the Latino vote, representing a massive 14 percentage point increase over the 2020 election.

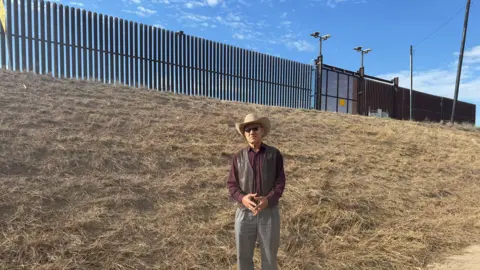

Bernd Debusmann/BBC News

Bernd Debusmann/BBC NewsLocals say the victory in Starr County is due in large part to Trump's stance on the border.

“We live in a country of order and laws,” said Demissio Guerrero, a naturalized US citizen originally from Mexico who lives in the town of Hidalgo, across the international bridge from the cartel-plagued Mexican city of Reynosa.

“We have to be able to determine who's in and who's out,” Guerrero added, speaking in Spanish, a few meters away from a long brown metal barrier marking the U.S. end. “Otherwise this country will be lost.”

Like other Trump supporters in the Rio Grande Valley, Guerrero has said — repeatedly — that he is “not against immigration.”

“But they have to do it the right way,” he added. “Just like the others did.”

Marissa Garcia, a resident of Rio Grande City in Starr County, agrees that Trump is “not anti-immigrant or racist at all.”

She added: “We are tired of them (illegal immigrants) coming in and thinking they can do whatever they want with our property or land, and take advantage of the system.” “It's not racist to say things need to change, and we need to take advantage of that too.”

Support for deportations is so strong that the Texas state government offered Donald Trump 1,400 acres (567 hectares) of land just outside Rio Grande City to build detention facilities for illegal immigrants — a controversial move that the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas described as “Mass incarceration” would “fuel civil rights violations.”

While the parcel of land — located between a peaceful farm-to-market road and the Rio Grande River — is currently quiet, city officials believe it could ultimately be a boon to the area.

“If you look at it from a development perspective, it's great for the city's economy,” Rio Grande City Manager Gilberto Milan told the BBC.

“It's clearly a detention area that has some negative connotations,” he said. “You can see it that way, but obviously you need a place to house these people.”

Bernd Debusmann Jr/BBC News

Bernd Debusmann Jr/BBC NewsThe number of migrants arriving through Mexico is trending sharply lower – with crossings last month at their lowest levels since January 2020.

But the issue is still alive on the streets of cities like Chicago, far from the southern border.

It is one of several Democratic-run cities that have enacted so-called “sanctuary city” laws that limit local police cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

In response, since 2022, Republican governors in Southern states like Texas and Florida have sent thousands of migrants north on buses and planes.

Tom Homan, Trump's pick to lead border policy, told a Republican crowd in Chicago last month that the Midwestern city would be “ground zero” for mass deportations.

“On January 21, you will have a lot of ICE agents searching your city for criminals and gang members,” Homan said. “Count on it. It will happen.”

Many local politicians, including Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson and Gov. J.B. Pritzker, have continued to support sanctuary city laws, here called the “Welcoming City” law.

But this policy is not universally popular. In November, Trump made gains in several Latino neighborhoods.

Recently, two Hispanic Democratic lawmakers tried to change the law and allow some cooperation by Chicago police with federal authorities. The measure was blocked on Wednesday by Johnson and his progressive allies.

Mike Wendling/BBC News

Mike Wendling/BBC NewsFor now, congregants at Lincoln United Methodist are making plans and watching carefully as they see how Trump's plans will play out.

“I'm afraid, but I can't imagine what undocumented people feel,” said De Camacho, a 21-year-old legal immigrant from Mexico who was among the worshipers at the church on Sunday.

Mexican consular officials in Chicago and elsewhere in the United States also said they are working on a mobile app that would allow Mexican migrants to warn relatives and consular officials if they are detained and potentially deported.

Officials in Mexico have described the system as a “panic button.”

Organizers at Lincoln United are also reaching out to legal experts, advising locals on how to take care of their finances or arranging child care in the event of deportation and helping to create identification cards containing details of the migrant's family members and other information in English.

Many second-generation immigrants here said they are working on improving their Spanish, so they can relay legal information or translate to immigrants being interviewed by authorities.

“If someone with five children is taken away, who will receive the children? Will they go to social services? Will the family be divided?” said Rev. Emma Lozano – mother of Rev. Tania Lozano of Washington and a longtime community activist and church elder.

“These are the types of questions people ask,” she said. “How can we defend our families – what’s the plan?”