Patricia Pascal

Patricia PascalWhen she was a little girl and took a long time to get ready for school, for family gatherings, or to sing in the church choir, Carmen Souza, a Cape Verdean musician, was often asked to say “Ariob.”

What she didn't realize until years later was that the Creole word came directly from the English word for “hurry.”

“We have a lot of words that come from British English,” Souza, a jazz singer, songwriter and instrumentalist, tells the BBC.

“Salong” means “very long,” “fulespide” means “maximum speed,” “streioei” means “straight,” “bot” means “boat,” and “ariope” – which I always remember my father saying to me when “He wanted me to pick up the pace.”

Ariope is now one of eight songs Sousa composed for the album Port'Inglês – meaning port in English – exploring the little-known history of the 120-year-old British presence in Cape Verde. It started as research for a master's degree.

“Cape Verdeans are very connected to music – in fact, we always say that music is our biggest export – so I wondered if there was a musical influence as well,” she says.

There are very few recordings of the compositions of the time – Sousa discovered that the American ethnomusicologist, Helen Heffron Roberts, recorded some in the 1930s but they were on wax cylinders that were too fragile and could only be heard in person at Yale University in the United States. .

So instead of rearranging old recordings, Souza and her musical partner Theo Pascal created new music inspired by the stories she had experienced.

It combined jazz, English sea shanties and Cape Verdean rhythms – including the funana, played on an iron bar with a knife and accordion, and batok, played by women and based on African drum rhythms.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Cape Verde Islands are located about 500 kilometers (310 mi) off the coast of West Africa. It is mostly arid, with limited arable land and prone to drought.

But it represents a strategic midway point in the Atlantic, and was initially controlled by the Portuguese as they traded between Southeast Asia, Europe and the Americas – in spices, silk and slaves. With the abolition of the slave trade, Cape Verde declined.

Cape Verde remained a Portuguese colony until 1975 – but during the 18th and 19th centuries, British traders settled and Cape Verde once again became a busy crossroads.

The British came for cheap labour, goats, donkeys, salt, turtles, amber and archil, a special ink that was used to make British clothing.

They built roads and bridges, developed natural harbors – which became known as Port Ingles – and established coal supply stations with coal brought from Wales.

The port of Mindelo on São Vicente became a vital refueling station for steamships carrying goods across the Atlantic or to Africa – and an important center for global communications with the arrival of a submarine cable station in 1875.

Sousa's exploration of the British presence in Cape Verde soon became personal.

“When I started researching, I found a lot of personal connections,” Souza says, including the fact that her grandfather loaded coal onto ships in Mindelo.

This inspired her to write Ariope – the story of an older man goading a young man who prefers to remain in the shadows as he plays his guitar to “ariope”. British ships are coming and the sailors don't like to wait – “fulespide, streioei” goes the song.

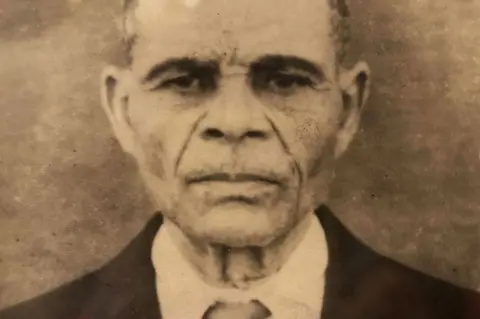

Carmen Souza's family

Carmen Souza's familySouza imagines her grandfather's spirit in the song. He played the violin – and was known as a great storyteller.

“I was told that if you had to walk kilometers with him, you wouldn't notice the distance, because it would be one funny story after another.”

Sousa is part of Cape Verde's large diaspora. Born in Portugal, she now lives in London. According to the International Organization for Migration, there are about 700,000 Cape Verdeans living abroad – twice their number at home.

Historically, people have had to move for work due to famine, drought, poverty and lack of opportunities.

This movement has contributed to the islands' deep and rich tradition of strongly distinctive music, including the melancholy morna made popular by singer Cesaria Evora and declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2019.

The composer behind many of the songs that made Évora an international star was Francisco Belleza – also known as P. Liza. He revolutionized Morna and was one of Cape Verde's most influential Morna writers, composers and singers.

According to Souza's research, he also viewed the British presence as more beneficial than the Portuguese presence – at least for middle-class Cape Verdeans.

Sousa Amizade's track, a mix of funana and jazz, was inspired by B. Lisa's admiration for the British. He composed the murna – Hitler ka ta ganha goera, ni nada, meaning “Hitler will not win the war” to show solidarity with the British people during World War II – and even raise money for the British war effort.

Sousa found that the ports were “an important center for musicians” who flocked there to learn music—and instruments—for visiting foreign sailors.

They mixed it with Cape Verdean rhythms to create new sounds. The mazurka – derived from a Polish musical form – and the contradanka from the British quadrille.

Early written records of Cape Verdean music are rare – Portuguese colonists did not document life and society in Cape Verde other than tax and commodity records.

They also banned batok – for being too loud and too African – and funana because its lyrics challenged social inequality.

But Sousa found an interesting entry in the memoirs of British naturalist Charles Darwin, who arrived in Cape Verde in 1832 — the first stop on his famous Beagle expedition to study the living world.

He describes an encounter with a group of about 20 young women who, Darwin wrote, “sang with great vigor a wild song, and beat their hands upon their feet.”

Sousa says this is likely an early performance of batok music, and she was inspired to write “Saint Jago” by Darwin's accounts of the warm hospitality he received in Cape Verde.

Many young musicians in Cape Verde tend not to play the old rhythms of the islands, and some of them, like contradance, are slowly fading away.

Sousa hopes that her album Port'Inglês will inspire younger generations that “there is a way to do something new with traditional genres.”

“I always bring in some different elements — improvisation, piano, flute, jazz harmony — so that the music goes through another process of intonation.”

Carmen Souza's Port'Inglês was released through Galileo MC

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC